Read Malawi!

Hailed a Triumph

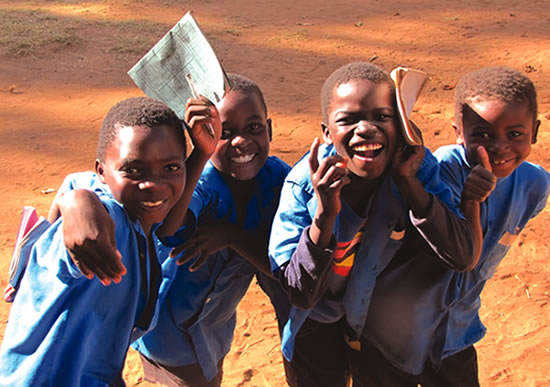

The faces of 150 primary school children stare into a camera as they sit on a crumbling concrete floor, their teacher standing nearby at the front of the room. There are no desks or pencils in this classroom and the yellow walls stand void of posters, student artwork, or any other material. It is easy for outsiders to look at these pictures and see only what the children of Malawi don’t have.

Dr. Misty Sailors and her colleagues on the Read Malawi! research study encountered Malawian children living in a peaceful, multilingual country, with a rich story-telling culture, caring adults in their community, and a strong desire to learn.

“We operate from the notion that we don’t go into a country and simply implement practices there. We work with local leaders to identify educational challenges and issues. And, then together we search for solutions, merging local knowledge and Western practices. That combination becomes a powerful intervention for teachers and kids,” Sailors, a professor of reading and literacy studies in the department of Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching in the College of Education and Human Development stated.

Sailors began this project in 2009 and served as the primary investigator on the $8 million U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID), Textbooks and Learning Materials Program, also known in Malawi as the Read Malawi! research study. Initially, the scope of the project was limited to working with local educators to develop and distribute reading books throughout the country. Instead, the project expanded after Sailors met with representatives of the Malawian government.

“They said books are great, but we also need you to work with our teachers and our principals,” Sailors said. “We need you to work with our school inspectors. Everyone needs to know how to implement the books. We need you to advance our printers to develop the capacity to print all these materials. And we need you to work with our community so that the community helps the schools,” Sailors continued.

In addition, the Malawian government was interested in academic studies that described whether the project helped build capacity, whether it was cost effective, and whether the program worked for children and teachers in the classrooms as well as the Malawian community.

The Malawi Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, as well as the Malawi Institute of Education, and two Malawian teacher training colleges served as the key collaborators on the production of the teaching and learning materials and the development of the literacy curriculum.

The Creative Centre for Community Mobilization, a nongovernmental organization in Malawi, worked with the community to support the schools in the implementation of the intervention. U.S. collaborators included the University of Texas at Austin, the University of California Berkeley, Intel Corp., as well as the UTSA Institute for Economic Development (IED), among others.

The first phase included working with local teachers and artists, who would serve as the authors and illustrators.

“The teachers wrote about the kids’ lived experiences and they wrote about things that were unique to the Malawian child’s lives,” Sailors stated.

According to Sailors, the material needed to not only reflect the children’s culture and experiences, but maintain an instructional value to the teachers so that reading skills and strategies could be taught using the books.

The brightly colored books illustrate the rural Malawian landscape, with children or animals as the main characters.

Many of the stories in the books represent Malawian folk tales that the children will resonate with. Other books demonstrate an envisioned life in Malawi. One book, for example, “What can girls do?” illustrates traditional roles of women in Malawian culture, as well as non-traditional roles for girls, such as becoming president of the country.

Some of the books are printed in Chichewa, Malawi’s national language and others in English, the official language. Curriculum specialists at the Malawi Institute of Education worked closely with Sailors and her team to develop guides for the teachers that accompanied the books.

According to Sailors, although other U.S. project researchers suggested printing the material in South Africa as a cost effective alternate, Sailors dissented stating that the printing in Malawi would be an investment in the economy.

The second phase involved training teachers and school leaders how to use the new teaching and learning materials, and organizing the community around supporting the literacy intervention.

“The government knew that unless you involve the community, your intervention is not going to be successful,” Sailors affirmed. “So it was the village leaders, the traditional chief, the mother groups, the school governance board, the PTA, and the principals, all involved and participating. It was amazing to see everyone holding everyone else accountable,” Sailors continued.

The government of Malawi then distributed the 5.2 million books and instructional materials to 1,200 schools. The team then set out to conduct their research on the effectiveness of the innovation in the third phase.

The project was concluded in Dec. 2012, but Sailors and her colleagues, both here in the United States and in Malawi, continues analyzing data and drafting academic findings related to their experiences.

“Malawians told us over and over that our collaborative program was not like anything they had ever seen before,” Sailors stated.

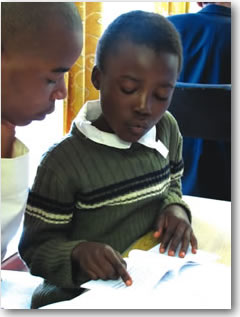

According to Sailors, working with the teachers and the Malawi community enabled the success of the Malawi research study. The study was a new experience for the teachers who had access to over 4,000 books in their schools.

“Together, our international team worked with teachers to flood their school and classrooms with books. In all the schools where we placed books, we taught the teachers how to utilize the books, and the school leaders how to support the teachers in learning to use the books,” Sailors stated.

Sailors and her collaborators are in the process of writing and reviewing several studies that describe how the Read Malawi! intervention increased student reading achievement, improved teacher’s reading instruction, increased community participation in schools and built capacity within the organizations and institutions with whom it worked.

Additionally, the team is also exploring the short-term benefits of intervention in the reduction of dropouts in schools where Read Malawi! was implemented and the long-term benefits of using the program to reduce the government’s educational expenditures.

According to Sailors, each of the participating team members (U.S. and Malawian) were exposed to an array of experiences, such as the mechanics of maintaining large data sets across international team members and staying organized in the field, as well as the logistics of arranging international travel, interacting with people from a different country and learning to live in an unfamiliar environment.

Lorena Villarreal, a graduate student working with Sailors on the research study, said she learned about resourcefulness, commitment and the difference a unified community could make in the education of children.

“The people of Malawi want everybody to learn to read, and they’re willing to go above and beyond to make sure that not just some but everyone in the community gets involved. It was amazing,” Villarreal stated.

Villarreal advises students to go into a research opportunity with an open mind because that is how true learning and appreciation for what the culture and community has to offer is realized.

“In the Western world we often have preconceived notions about the things we will experience in developing countries. I did not want those notions to impinge upon my time in Malawi. This allowed me to have a positive learning experience and enjoy my time in the community,” Villarreal said.

Furthermore, Sailors offers one key bit of advice for those inquiring about international research studies and that is to develop strong working relationships and trust with your collaborators.

“Our partners would sometimes go for days without electricity and subsequently no Internet. So, here we are in San Antonio and we’ve got deadlines and we’re not hearing from them. But we trust that it’s something beyond their control. And you start worrying then, because the daily contact has been broken. You worry about them, because they’re not just our colleagues, they’re our friends,” Sailors continued.

According to Sailors, although the USAID contract has ended, evidently, the relationship with her Malawian colleagues continues to be collaborative and enriching as they engage in research composition.

Error processing SSI file