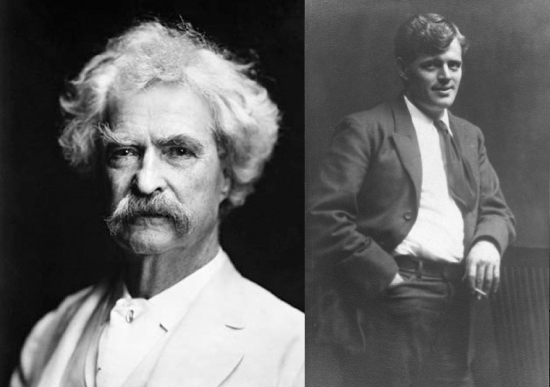

“Tramps Abroad”

Jeanne Reesman on Mark Twain and Jack London

Taken by Jack London in Korea, 1904. Courtesy of California State Parks, 2012.

Offering something new to say about America’s favorite writer was a challenge for Jeanne Campbell Reesman, professor of English, Jack and Laura Richmond Endowed Faculty Fellowship in American Literature and Ph.D. Graduate Advisor of Record. She seems to like challenges—Her latest book is titled Mark Twain vs. God: The Story of a Relationship, to be released in 2015.

Reesman, who has written, edited or contributed to more than 50 books on late 19th- and early 20th-century American authors, noted, “There have been important books and articles on Twain and religion, but it seems many scholars have not wanted to talk about Twain and God directly, especially Twain’s attacks on God. Twain is supposed to be the kindly old humorist of traditional American culture, a sentimental recorder of carefree frontier boyhood, but that’s just not the complete Twain,” Reesman observed. “Far from it.” She was not surprised to discern through her research over the years that Twain seemed obsessed with God: “I also thought that as Twain was one of the most conspicuous people on the planet in his day, God must have noticed him too.”

Twain believed in God, but he doubted His nature. Brought up in a strict backwoods Calvinism in a rough river town environment in which slavery and other social ills of the era existed, Twain experienced a difficult childhood, with contradictory messages about God from his believing mother and atheist father, and his father died when Twain was 11 years old. From the cradle he struggled with finances, illness and early deaths—he himself was 2 months premature and not expected to thrive. But his animus at God was not just personal; he saw God as unfair to everyone, creating humans and then punishing them for being human.

“Seizing on such stories as the fate of Adam and Eve, Twain at times regarded God as a vengeful, petty, cruel failure of a Father who could not be trusted,” Reesman commented. “As he said, ‘I was educated; I was trained. . .; I knew that in Biblical times, if a man committed a sin, the extermination of the whole surrounding nation—cattle and all—was likely to happen. I knew that Providence was not particular about the rest, as long as He got somebody connected with the one He was after.’” In Letters from the Earth, Noah is ordered to turn around and go back for the housefly, since without it many of the worst pestilences would not exist. Twain used Satan as a narrator and humor itself as literary devices to mask his critique of God.

“Yet,” Reesman added, “Twain also experienced powerful desires to believe: his best friend was a clergyman; he loved to play the piano and sing old hymns; and he tried his hardest to be a Christian with his beloved wife, Olivia. He certainly had a strong Calvinistic sense of guilt, but it seems he wanted a better God than the one he was taught about as a boy. On his deathbed, his last words expressed his hope to see his daughters in the afterlife.”

Twain’s faith was not in the church, but in a small number of individual figures such as Joan of Arc, about whom he wrote a serious biography based on the trial records. Twain portrayed ancient and modern concerns: the court of King Arthur taken over by a “Connecticut Yankee”; politics and finance in Washington, D.C., in The Gilded Age; new forensic discoveries in Puddn’head Wilson. He had a fascination with dreams, space travel and new inventions (to lose money on). From beginning to end, his work reflected the intense influence of Darwin (as in “Was the World Made for Man?”).

“Twain formulated a new vernacular national voice for American literature, most of all in the person of Huckleberry Finn. Black voices are strongly present. His fame is based on his portrait of the Mississippi River and its great valley and its fertile tales,” Reesman claimed. For this, William Dean Howells called him “the Lincoln of our literature.” But, she added, Twain also traveled the globe, as he relates in Following the Equator: Anti-Imperialist Essays and A Tramp Abroad.

Like scientific researchers, literary scholars pursue theories that must be explored and tested through research and evidence. But instead of working with specimens in petri dishes in a laboratory, the literary scholar delves into letters, archives and artifacts.

“Primary research is firsthand materials, manuscripts, unpublished letters, notes, author’s files. I’ve even looked at the matchbooks that Jack London made notes in,” said Reesman, a leading scholar on Jack London in addition to her work on Twain. “It’s imperative for literary scholars to go to the archives to create an accurate edition with scholarly notes or write a biography, and just to understand the subject when it comes to literary interpretation and criticism, which is secondary research. A lot of times, students don’t realize that the book in their hands may not be what the author wrote.” Primary research also includes the study of historical contexts of literature. For this book on Twain, Reesman will be doing a combination of primary and secondary research.

Mark Twain and Jack London. Courtesy of California State Parks, 2012.

Her primary research will take her to the Huntington Library in Southern California to delve into the Mark Twain archives and to Elmira College in New York to examine Twain’s annotations in his books. She will be applying for grants to finance her research trips. She gratefully acknowledges the endowment research funds she receives as the Jack and Laura Richmond Endowed Faculty Fellowship in American Literature. She first met the local donors when Jack Richmond’s interest in Jack London caused him to contact her in the 1980s, soon after she first arrived at UTSA.

"In the humanities the grant model is very different from that in science and engineering,” explained Reesman. “Very rarely does somebody get a $100,000 award. But we don’t buy equipment, and we don’t run labs.” The usual NEH grant is $12,000 to $24,000. Throughout her career, Reesman has received $305,900 in grants from the NEH, the Fulbright Program, the Huntington Library, the American Philosophical Society, the National Science Foundation, and UTSA, as well as from private donors, to conduct research, teach abroad and lecture at conferences on American authors. A large part of those funds, $80,000 from private donors, went towards the research and photo printing for her book Jack London: Photographer, which she co-authored with Huntington Library curator Sara S. Hodson and photographer and photo preservationist Philip Adam.

As Reesman noted, “While London is largely defined by his naturalistic, Darwinian tales of struggle and survival, he was also a journalist, as was Twain when he started out. He coincided with the advent of film-based photojournalism. London covered the Russo-Japanese war in Korea in 1904 for Hearst newspapers. A year earlier, he had captured slum life in the East End of London in his illustrated book The People of the Abyss. In 1907-09 he sailed the world with his wife and a small crew on their sailboat, Snark, photographing people from Hawai’i to the Solomons. London took great care to portray with dignity and respect the people he met during his travels abroad and increasingly shed his earlier racialistic views as he encountered more and more the results of colonialism in the South Pacific. His several series of portraits reveal his photographic intent. He did not use the standard poses for ‘natives.’” He was also a primary photographer of the San Francisco Earthquake on April 18, 1906. Jack London, Photographer took 12 years to accomplish: “We had to raise money because we made silver gelatin fine prints, sometimes using original negatives. We also had to do quite a bit of research on early photography and cameras.”

Reesman explained that she was drawn intellectually to London at an early age for the same reasons many other readers throughout the world have been touched by his work—he represented transformation and freedom. She said that the snobbish critical views of Jack London in the past made it fun to advocate for him. “He wasn’t considered fit for the college classroom. He was too Western, too popular, too socialist, too women’s rights. Unlike Twain, who was taken up by the Eastern literary establishment, London remained outside respectability.”

“But it’s not really a logical choice as to how you choose an author,” she added, “because at a certain level of performance you have to develop an instinct, almost a sense of kinship with an author, to really ‘get’ him or her and be able to see patterns. It’s similar to the instinct good teachers have for their students. It takes time and work as well as inspiration.”

“I’m drawn to writers who are complicated and contradictory,” Reesman said. “In them I have the opportunity to discuss both narrative and ethical issues.” She sees Twain and London as related in fundamental ways: they were famous for writing about a region, even a specific river; they were known for boys’ books but were writing for adults; they were tremendous observers not just of “nature” but of human nature in frontier environments; they were strongly influenced by Darwin; they struggled with spirituality; they endured the terrific financial depressions of the 1890s; and they were social critics. And each held contradictory racial views, especially London. Twain’s views on race were progressive but not really egalitarian: “I believe I have no prejudices whatsoever. All I need to know is that a man is a member of the human race. That’s bad enough for me.”

“Everyone agrees there is a benefit to the work being done in the humanities. But they aren’t usually sure what it is. Can it make us better people? If Twain were called as a witness, he would say no, but then, if that were so, why did he bother to write? We have to look at how writers like London and Twain who transgressed certain rules in literature helped make way for breakthroughs today.

“As one of the arts, literature tells the human story from lots of different perspectives,” Reesman concluded. “It gives pleasure. And it does instruct. Outcomes of all human stories are based on many factors, including biology and environment, but also on moral and ethical choices that the characters make. London called literature ‘the language of the tribe.’ Authors don’t just entertain people with great works of literature. They promote a common language of humanity.”

Error processing SSI file