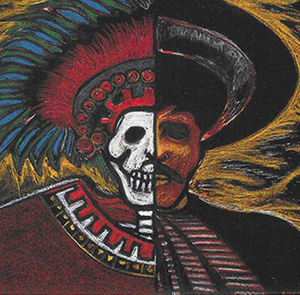

Mestizo

My interview with J.P. Santos began with an exhilarating, and impassioned conversation concerning the mythos behind the Mexican historical figure, Doña Maria, often referred to as La Malinche. Noted in History as the treacherous liaison, and interpreter, to the Spanish conquistador, Hernán Cortéz, La Malinche is often portrayed as a traitor to the Mexican people. Her liminal position is often perceived as the direct cause for the success of Cortez’s conquest as well as the subsequent Spanish colonization of the Aztec Empire. Acting also as Cortez’s mistress, La Malinche eventually gave birth to a son who has become known today as the first mestizo, a term which Santos explains, is used specifically to define a person of both indigenous and European descent. The vast epistemology that has developed in the wake of the term mestizo, as well as the ramifications for its social context and function are what provide the zeal that drives Santos’ scholarship.

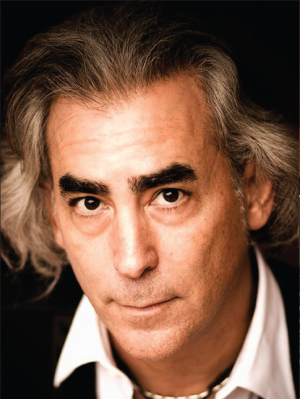

When asked how his eclectic range of study will translate into the UTSA dialectic, Santos answered by stating, “I am not a conventional academic by any means. While I do plan to examine the theme of mestizaje, and the way that it has been informed by Chicano and Latin Studies, I am more and more interested in the extent to which mestizaje is a process and how mestizo identities, as a framework, applies to a whole series of cultural expressions in the era of globalization. The idea of mestizaje is proving to be, in fact, a kind of a fundamental process in not only shaping out what Mexico, Texas, and especially South Texas have become, but what America has always been.”

As Texas has a seemingly larger part to play in identifying these processes, I was compelled to ask whether or not Santos felt Texas’ situation was unique as a result of colonization, or if he felt that it has to do with its close proximity to the border. Santos replied by stating, “Mestizaje has always been a primitive driver in the civilization process and cultural expression; in other words, the process of mixing of people. We are now learning more and more about how this complicated scenario prevailed even in the earliest of human civilizations. There is now a vast amount of genetic evidence that suggests that there was extensive “mixing” going on in Iberia. Preceding the discovery of the New World there had been a very profound and deep mixture of culture and civilization, which included the Moors, Jews, and the Christians in a series of incursions. So, interestingly, the story of Iberia is connected to the story of Mexico.”

Guided by an interdisciplinary approach with which to approach the plethora of ideologies associated with mestizaje, Santos plans to shift its center to encompass other cultures that have been affected by colonially imposed ideologies. Of this impact, Santos states, “That is why I am interested in how the theme is now emerging. I have focused on new kinds of historiographies, new types of creative work around the world, such as Central Europe, Africa, and South Asia.”

“The idea is that San Antonio has a role to play in developing this new kind of discourse, in a sense, for the nation and the rest of the world. Scholars might come to UTSA specifically to study this phenomenon.” Santos stated that with increased interest and awareness, San Antonio will, no doubt, become the hub for this type of scholarship. Working with the College of Education and Human Development’s Bicultural Bilingual Program, as well as UTSA’s Honors College, Santos has the advantage of taking different aspects from ideologies concerning mestizaje, and, by doing so, hopes to create an eminent seat for this scholarship.